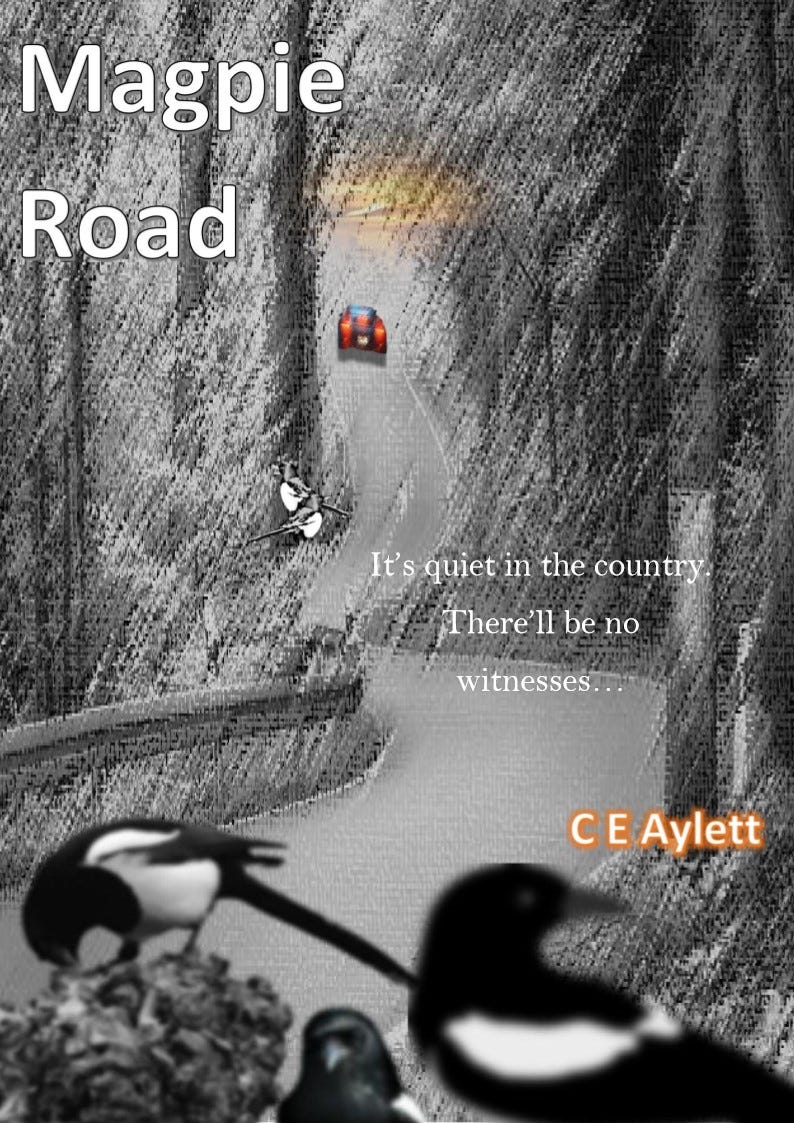

Magpie Road By C E Aylett

It's quiet in the country. There'll be no witnesses...

Contemporary Mystery. Originally published in Bandit Fiction Presents.

The bird was pinned to the oak tree across the road. A magpie, the nail driven into the base of its neck, head slumped to the side, its black beak pointing sorrowfully to the ground. Both black wings had been splayed over the thick, rough trunk.

Kerry spotted the grisly sight from the kitchen window, and her hands flew to her mouth, dropping the breakfast dishes. Soapy water exploded from the washing-up bowl with a splosh, soaking her shirt.

“Damn!” She grabbed a towel and wiped herself down.

Clarissa laughed. “Kekky wet.” The toddler pointed at Kerry’s blouse.

“Yes, darling. Mummy – Mummy’s wet. Can you say Mummy? Mumm-ee.”

The little girl went back to squashing splodges of porridge on her high-chair table with a chubby forefinger.

Kerry blew out a sigh, lifting her frizzy brown fringe into the air. One day…

The bird tree grew diagonally opposite their house on the sharp curve of a grassy chicane, just outside the village and just outside the thirty zone. Every morning, Kerry carried out the last night’s leftovers, dumped them onto the little wooden platform attached to the trunk, and returned to her cottage to watch. A furore of crows, tits and magpies swooped in, each one plucking up a piece of food and swooping off before the next one landed. Sometimes, she picked up Clarissa from the high-chair and placed the child on her hip so they could watch them together. Kerry adored the girl’s silky, blonde hair brushing her cheek, but she certainly wouldn’t be doing that this morning.

A tumult of questions bombarded her mind: Who would carry out such a heartless act? Why would they tack it up outside her house where Clarissa could see? And how on Earth did they catch the poor creature? It had to be either with food or some shiny trinket. But for what? Kerry and Paul had kept their heads down since moving into their cottage and were unfailingly polite to those they met in the village. Folk were seriously deranged these days. The cruelty of people toward animals and children!

“Tack you up to a blooming tree,” she muttered, scraping down the last bowl of leftovers into the tub with increased vigour.

Kerry would have preferred to put the bird table in her own front garden, but she didn’t have one. The small patch of gravel in front of their brick cottage finished right on the road, save for a slither of pavement. Not a terribly busy road, but a dangerous one, nonetheless. It was long and straight leading away from the small town, with the zig-zag bend – where her house stood – leading into it. Cars often roared up to the turns from the straight run and slammed on their brakes at the last moment. Kerry would steel herself for the worst and sprint to the window to see if they’d skidded off the lane or collided with another vehicle.

This morning, the sun beamed strong and sharp through the flapping leaves; no haze of cloud today. Across the road, the usual scrimmage of birds hopped about the surrounding branches of the smaller forestry waiting for their breakfast, quite unperturbed by the corpse pinioned beside their empty platter.

Kerry sighed. “Okay, okay, I’m coming.”

She hastened to the cupboard under the stairs for a claw hammer so she could take the poor, lifeless thing down, unable to bear the thought of an insensible frenzy taking place alongside it.

Despite the occasional kamikaze traffic, there was an advantage of living where she lived – no neighbours for five hundred yards, just a hill at the back of them and a field across the road behind the line of oaks and smaller shrubs. Nicely tucked away in the countryside. Concealed from prying eyes. The last thing they welcomed was any outside interference.

She and Paul had wanted a home even farther off the beaten track, but time constraints meant certain sacrifices, and finding somewhere more suited to their tastes hadn’t been possible. They needed to move, and fast. They had a child to shelter and responsibilities to meet.

The desire for a family had gnawed mercilessly from the inside-out for years. Failure to produce one became a weight too much to bear amongst the carousel of friends who had son after daughter, daughter after son. Endless christenings and baby showers had spun Kerry into such a tizzy, for they had tried and tried to have a baby without success.

The day Clarissa arrived, the darkness of disappointment and worthlessness lifted its veil and the light of hope finally warmed their smiles. Yet, the opportunity to bring a child into their lives still caught them by surprise. They hadn’t been prepared, not in the way new parents should. But that’s how Chance worked.

She finished off loading the dishwasher. Bracing herself for the unsavoury task ahead, she dashed a quick kiss on the toddler’s head.

“Be right back, my angel.”

Grabbing a carrier bag from under the sink to put the bird in and, seizing the tub and hammer, she headed out the door.

Kerry thought she might be sick. The nail had been hammered in fast and she had to push the claw against the neck of the bird to leverage it out, partially severing its head. Flies buzzed around, crawling over the open wound. Were it not for her sleeping tablets, perhaps she would have heard the sick culprit pounding away during the night. Her own idiocy chilled her; what if Clarissa had woken? She vowed never to make that mistake again.

This was one time when she wished Paul had said ‘no’ to his new boss and stayed home. She would have had no qualms leaving this job to him.

With one last hard yank the nail came out, and the carcass fell to the ground with a soft thump. In the distance, a car approached and so she hurried, aghast at the idea anyone seeing the monstrosity would assign her as the responsible party. She placed her hand inside the bag, using it as a glove to pick up the remains, and wrapped the dead avian in the plastic.

Only once she had stepped onto the tarmac to return to the house did she realise the rumble of the engine was closer than she’d estimated. And it wasn’t slowing down.

“Idiot,” she muttered and quickened her step, sure she would make it in time. But no; the driver sped up. “What on Ear–?”

The slam of speeding metal tossed her into the air and she shot over the roof of the vehicle while the car roared off towards the village. She bounced hard upon landing. So hard the impact might even have catapulted her soul out of her body for an instant.

Kerry had never known pain like it. It rang so irreversibly through her bones, her teeth, her hair, even out through her fingertips. A burning pain, like when one hits their funny bone on the corner of a wall, but this agony was everywhere and unending.

She lay there for what seemed an eternity, as motionless as the magpie in the bag still wrapped around her wrist.

What followed were glimpses and confusions, people around her, legs moving this way and that. Impossible to hear anything and yet there seemed a terrible din. The same thoughts wheeled around her fragile consciousness: the baby’s on her own in the house; she might be crying; she might need someone. But Kerry couldn’t move, couldn’t talk, and the day drew darker. Surely it was still morning, though, wasn’t it?

Just before the blackness ebbed to completion, through the forest of legs and bottoms and slowed traffic, before the sirens peeled in the distance, growing closer, Kerry saw a man walk through her front door. A man she knew, perhaps. She wasn’t sure. With relief that someone would take care of the baby, she gave in and the gloom descended.

It stayed that way for almost two years.

#

“Lucky you’re still alive,” the doctor said upon her rousing in hospital. “Still a long way to go, however. Best be calling this place home for now.”

At first, she thought little of only Paul visiting. She felt weak, befuddled. It was important not to overcrowd her, they said. The police took a statement but decided they would return when her memory had sufficiently recuperated. Her body’s recovery and the accompanying physio exhausted her, leaving no energy to think outside of the nurses’ instructions. And the meds didn’t help in keeping a clear head, either. As the weeks stretched out and she grew stronger, she urged Paul to bring in Clarissa for a visit. How she must have grown! Kerry wanted to hold her, stroke her hair, listen to all the funny things four-year-olds talked about. And above all, she was desperate to read her a story, just like they used to every bedtime.

Paul shuffled his feet and said it would be too much for the little girl, seeing Kerry so debilitated.

Kerry might have suffered some rudimentary brain damage, but at the very least she remembered how to tell when Paul was being mendacious. “Bring her in, Paul. I won’t hear any more excuses. Bring her in!”

“No.”

“Why not?”

He shook his gaze to the floor, wiped his face – his eyes – with his hand. Then he stalked out. What was going on?

It almost drove her insane lying in bed that afternoon, staring at the bland décor with no one to talk to, no one with whom to share her fears, worrying about Paul. Worrying about Clarissa.

Through the glass partition on the door, she saw nurses pass by to and from the ward, but none of them popped in to check her. Now she wished her husband hadn’t opted for a private room after all. She needed a distraction.

The previous occasions when she had shuffled down to the day room with her walking frame she had made slow progress. Watching the families visit their loved ones had relieved the boredom. In her more physically advanced state now, she could walk there with just a cane – albeit a little shaky. With nothing but her deepest insecurities brachiating around her unwanted enclosure, she got out of bed and put on her bathrobe.

The television was on when she arrived, but Kerry wasn’t interested in Bargain Hunt. People were much more fascinating. So, she found herself a quiet corner and simply observed them. Closest to her was a couple with a young child of about Clarissa’s age.

The wife wore hospital pyjamas and sat in an armchair with a drip stand alongside her. She had fallen asleep with her head flopped over the side and her arms drooped outwards over each edge like limp wings. It reminded Kerry of something grisly and prickled her skin all over, but she couldn’t pinpoint what. A glaucoma of the mind, pressing with importance yet camouflaged beneath a blur of light. She shivered.

The husband sat forward in another chair, taking great care to count numbers with their little girl while they played Snakes and Ladders. Waiting for Mummy to wake up, no doubt. The girl was on the floor, legs tucked into her side. Every time she leant over to move a playing disc, her long, dark bunches inadvertently moved the other counters around the board. Father and daughter rolled the dice and took her mother’s turns while she slept, the father patiently putting the tiddlywinks back to their rightful places each time the girl's hair moved them off point. Leant against the side of his seat was a shopping bag with a small, long-haired doll sticking out of one corner.

Tears prickled the back of Kerry's eyes. She didn’t even know if Clarissa had long hair, nor how Paul styled it – nor if he even bothered. He hadn’t brought her so much as a photograph. Why was anyone’s guess, but so many possibilities spun around in her mind it made her queasy. What if he’d met another woman and Clarissa called her Mummy? She wouldn’t remember how much Kerry had loved and cared for her back when she was just a toddler.

“Daddy, I need a wee,” the little girl said.

Her voice was so young and sweet it brought a gristle of sadness to Kerry’s throat, and she struggled to suppress the rising sob that ensued. Maybe this wasn’t such a good idea.

She stood up to leave, craving the isolation of her quarters once again.

“Come on, then,” the father replied. He linked hands with the child and went out into the corridor, the girl skipping, swinging her father’s arm.

As Kerry passed the sleeping mother, her foot clumsily kicked the bag containing the doll and it slumped to one side. The toy had blonde hair just like Clarissa’s – blonde hair that Kerry longed to stroke while she sang her lullabies. Checking no one was watching, she plucked the doll from the bag and stuffed it inside her robe.

#

Paul didn’t return until two days later. Two days! He came in with the doctor and an air clotted with unspoken words and lingering gazes, none of which lingered in her direction. It struck Kerry as ironic that the floor seemed so captivating to everyone but her in this hole. She was sick of the hospital and its walls, floors, beds, equipment and the snooty matron who worked every morning shift except for Sundays.

“Kerry…”

“Doctor?”

“Paul’s been struggling. He wanted me here when he told you–”

“Told me what?”

She couldn’t cope with any more medical complications or physio, and she refused to acknowledge the other possibilities that bubbled a toxic soup inside her guts. Everything would be fine, she chided herself. The worst is behind us. Unless…

“Have they found the driver?”

The doctor glanced at Paul, but it wasn’t reciprocated.

“It’s Clarissa.”

Kerry’s stomach dropped out like bathwater sucked down the plughole, and she trembled. The hairs on her arms stood to attention as if her whole being leant in to listen.

“Y-yes?” Her voice was a whisper.

The doctor looked at her husband again, but Paul’s stare remained fixed to the ground.

The medic let out a resigned sigh. “There’s no easy way to say this, so I’m just going to explain it to you straight.”

He paused, his glance once again darting in Paul’s direction. Nothing. Her husband kept his head cast downward, his hands in his coat pockets.

Kerry’s eyes shuttlecocked from one man to the other, her mouth dry as dust, desperate for someone to reveal what had happened, dreading what news it would be. “Wh-what? Tell me, what’s happened to her? Oh my god, is she dead?”

“You don’t have a daughter, Kerry,” he said with concern. “We’re aware of your medical history. The trauma to your head… it’s playing tricks on you, creating a reality that never existed. We’d hoped it would resolve itself, given time, but that doesn’t appear to be the case. I’m sorry.”

“But that’s not true.” She pushed herself to sit upright in bed. “Tell him, Paul. We have a daughter. Her name is Clarissa. She’s four years old. She’s real. She is! Paul!”

The doctor opened his mouth to speak.

“Actually, Doctor,” Paul said, “maybe it’s best if you left us for a moment after all?”

“Of course. I’ll leave you to talk. If you need anything…”

“I’ll push the buzzer. I know.” Paul said.

When he’d gone, Paul sat on the edge of her bed and took her shaking hands. Her eyes beseeched his.

“Th-the day of the accident,” he said, his tongue flicking snakelike across his dry lips,

“someone went into the house.”

Kerry gasped. A vision of the cottage and legs swam to the surface, of a man entering by the front door. “Yes, I remember. He went to get the baby.”

“Kerry, he took the baby.”

“Yes. Thank God. I was worrying.” She paused. “Paul? I don’t understand what the doctor meant.”

“He took Clarissa, Kerry. Kerry? I-I haven’t…”

Kerry stared at him as if he’d skewered the length of her spine with a javelin. The icy cloak of a darkness she knew intimately and hoped she would never know again crept down through her body, brushing her skin with the cold lips of loss. Death; forever her lover and never her friend. Here he came again.

“Haven’t what?”

Paul suddenly seemed grey and old. He bowed his head and rubbed his hands through his hair, cupping them around the nape of his neck. She almost didn’t hear him when he next spoke.

“I haven’t seen her since.”

“No… No! My angel…” This couldn’t be. It wasn’t happening. She was still in a coma, surely.

Kerry pulled off her covers and swung her legs off the bed, opening the drawers. She pushed the doll she’d taken just two days prior while trying to find a matching pair of socks and some pants. “We have to find her. What did the police say? They must have some idea where she went, who saw her last.”

Paul rose in alarm and moved round towards her, placing his hands on her shoulders, pushing her back down.

“Police? I couldn’t call the bloody police! Kerry!”

She stopped searching for clothes and gaped at him. The wrinkles in his face were deeper than she’d noticed since waking, sadness and defeat etched within. He’d given up long ago, she could tell.

“Think about it, love. I couldn’t call the police. What would I have said?”

Anger swelled inside her. “Our fucking daughter is missing! How about that one, Paul?”

Hot tears sprung up and ran down her cheeks. Stupid words; futile. She’d never see Clarissa again.

“But she was never ours, love, was she?” Paul’s face glistened wet, too. “She wasn’t ours to keep.”

A rush of unwanted memories hit Kerry hard: pregnancies, miscarriages. The stillbirth.

She put out a hand to steady herself on the bed.

‘I think it was her parents – her real parents,’ Paul continued, but his words were dull and distant, as if on the other side of a thick sea fog, there and not there. “I think they found us and plucked her out of the house while you were on the ground. Who knows how long they were watching us? Weeks, maybe months?

“I’m sorry, baby. There was only so much I could do on my own. In fact, I was hoping you wouldn’t remember. How insane is that? Hoping your wife will wake up with amnesia. So, I told the doctors we never had a daughter. You’ll have to pretend it’s in your head.

“I’m sorry, Kerry. I couldn’t call the police.”

I couldn’t call the police.

Those words echoed around her chasm of grief long after; years.

The memory of the magpie nailed to the tree struck Kerry like a blow to the cranium. The breath expelled from her, and one hand sprang up to her throat. She began to hyperventilate. Darkness cocooned her, simultaneously drilling into her core like a maggot in the belly of an apple, gnawing at her from the inside out. Merciless. Unending.

The fragments that remained of her heart almost disintegrated, imagining the years Paul had spent alone with this burden, unable to share it with any living soul but the one who lay dormant and silent within these walls. But there was no denying the saturation of love remaining within him. Love for Kerry. And deep regret.

Her breathing shallow and strained, Kerry turned to her drawer and took out the little blonde doll and other trinkets, laying them on the bed covers: a Ben Ten keyring; some sweets in gold wrappings; a mobile phone; a badge with Precious Parcels written on it; a baby’s dummy; a pot of strawberry body butter. She fiddled around with them, laying them all out on the bed in a circle, correcting their alignment with one another. When she had them positioned just as she wanted, she swapped them about and repeated the motion. And again. With each new round, her frantic breaths calmed a little.

Paul studied her, his face drawn. He put out his hand and gently squeezed her shoulder.